Why Am I Here?

Discovering our purpose to magnify God's glory in all of life, and why this is not narcissism but the path to true satisfaction.

The Question Beneath the Question

At dinner parties and networking events, we ask each other a standard question: “What do you do?”

The answers come easily enough. I’m a teacher. I’m an engineer. I run a small business. I’m a stay-at-home parent. These labels roll off our tongues without hesitation, locating us in the social landscape, giving others a way to understand where we fit.

But notice that the question is about activity, not existence. “What do you do?” is a manageable query. We can answer it with a job title or a role description. The question doesn’t dig too deep. It stays safely on the surface.

There’s another question lurking beneath it, one we rarely voice at dinner parties: “Why do you exist?”

This is a different sort of question entirely. It’s not asking about your activities but about your purpose—not what you do but why you are. What is the point of your existence? Why are you here on this planet at this particular moment in history? What is all this for?

The question haunts us. It surfaces in quiet moments—late at night when sleep won’t come, in the aftermath of loss, at midlife when the career trajectory flattens and we wonder if there’s supposed to be more. Viktor Frankl, the psychiatrist who survived Auschwitz, observed that humans can endure almost any “how” if they have a “why.” But when the “why” goes missing, even comfortable lives feel empty.

We instinctively recognize purpose in created things. A hammer exists to drive nails. A watch exists to tell time. A chair exists to support seated weight. When we encounter a designed object, we naturally ask what it’s for. We assume it has a purpose because it has a maker.

The same instinct applies to ourselves—but with far more urgency. We sense that we exist for something, that there must be some reason for our presence here. The longing for meaning is universal. Even those who claim life has no inherent purpose still live as though it does, getting out of bed each morning to pursue something they treat as important.

So why are we here? After establishing who we are in the previous chapter, we must now ask what we’re here for. Identity and purpose are intimately connected. If you’re an image-bearer of God, a new creation in Christ, a beloved child of the King—then surely that identity is meant for something. We weren’t created simply to exist but to express something, to do something, to live for something greater than ourselves.

Every worldview offers an answer to this question. But not every answer can bear the weight of a human life.

Unsatisfying Answers

The secular worldview, in its atheistic or naturalistic form, has a blunt answer to the purpose question: there isn’t one.

If the universe came into existence through random processes, if life evolved by accident, if human consciousness is merely the firing of neurons in a brain that will one day cease to function—then there is no cosmic purpose. You weren’t made for anything. You simply are. The universe is indifferent to your existence. When you die, you’ll decompose, and eventually the sun will burn out and the universe will proceed toward heat death, and none of it will have meant anything.

This isn’t a caricature of atheism. It’s what atheists themselves often acknowledge. The philosopher Bertrand Russell put it this way: “Man is the product of causes which had no prevision of the end they were achieving… his origin, his growth, his hopes and fears, his loves and beliefs, are but the outcome of accidental collocations of atoms.” The Nobel laureate physicist Steven Weinberg was even more direct: “The more the universe seems comprehensible, the more it also seems pointless.”

Now, many atheists insist that the absence of cosmic purpose needn’t paralyze us. We can create our own meaning, they say. We can choose what matters to us and live for that. But this is precisely the problem. Self-created meaning is no meaning at all—it’s pretense. If I decide that stamp collecting gives my life purpose, that doesn’t make stamp collecting cosmically significant. It just means I’ve distracted myself from the void.

And the void has consequences. A worldview of meaninglessness is driving a lot of people to do a lot of bad things. When people believe they’re cosmic accidents with no inherent purpose, they ask, “Well, so what? Why does anything matter?” This “so what” mentality produces passive resignation, depression, and sometimes outright destruction. If nothing matters, why bother being good? Why not pursue whatever fleeting pleasure presents itself? Why care about tomorrow if tomorrow is meaningless?

The statistics bear this out. The rise of secular worldviews in the West has coincided with unprecedented rates of anxiety, depression, and suicide—especially among young people who have absorbed the message that they’re accidents of evolution living on a pale blue dot hurtling through empty space. Meaninglessness is not a neutral conclusion. It’s soul-crushing.

But there’s another unsatisfying answer, one dressed in religious language: the Moral Therapeutic Deism we’ve encountered throughout this book. This pseudo-Christianity tells us that God exists to help us be happy, and our purpose is essentially to feel good about ourselves, be nice to others, and become the “best version of ourselves.”

This sounds more hopeful than atheistic meaninglessness, but it’s ultimately just as empty. It offers what the sermon source aptly calls “ice cream for the soul”—tasty in the moment but incapable of nourishing us. You can feel the logic: If life is about being happy and nice, then what? What’s the point of happiness? What’s it all for? The answer trails off into nothing.

Self-focused purpose cannot satisfy because we were not made for ourselves. We were made for something—someone—greater.

The Biblical Answer: To Magnify God

The biblical worldview offers a third option, one that sounds strange to modern ears precisely because it decenters us.

“Everyone who is called by my name, whom I created for my glory,” God says through Isaiah (Isaiah 43:7). Not for your glory. Not for your happiness as the ultimate end. For God’s glory. You were made to magnify him.

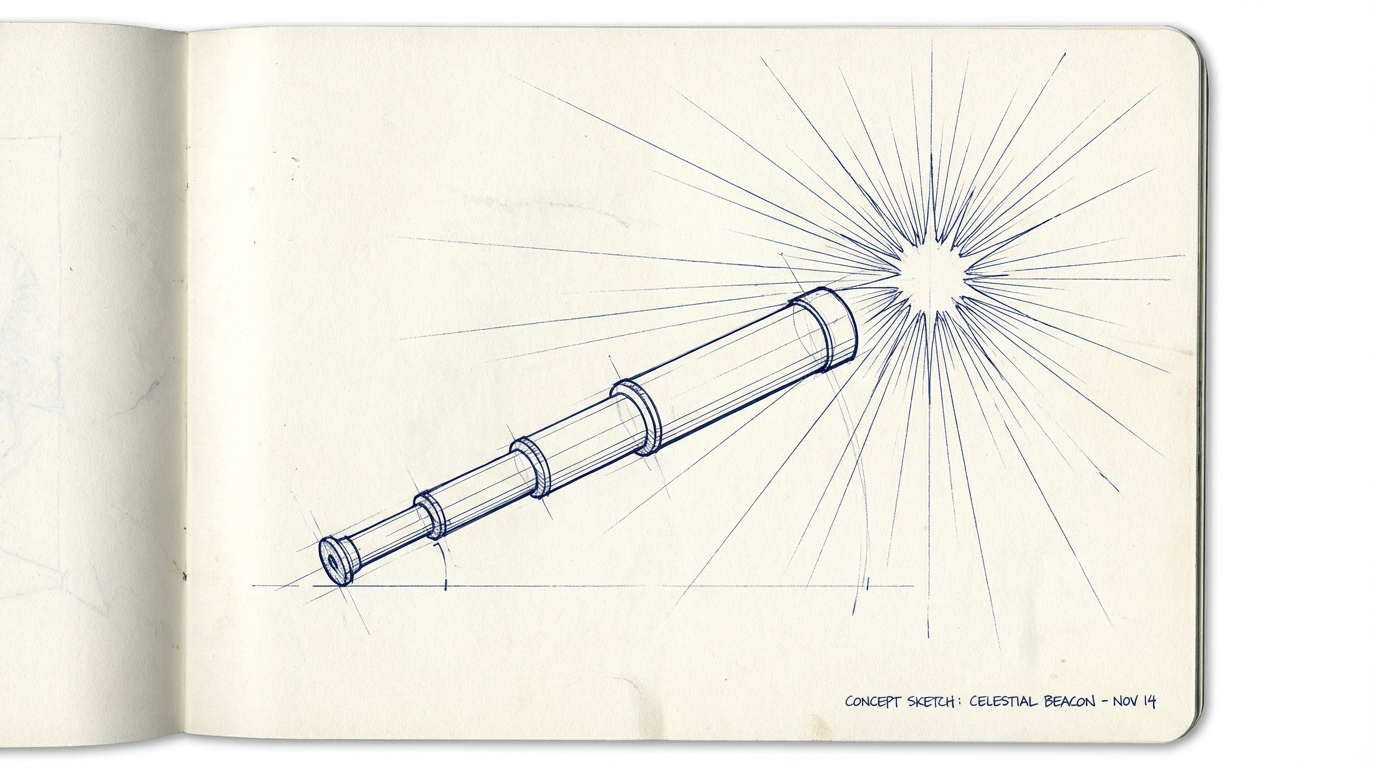

Magnify is an interesting word. It can mean two different things depending on the instrument. A microscope magnifies small things by making them appear larger than they are. A telescope magnifies distant things by making them appear closer than they seem.

When Scripture speaks of magnifying God, it doesn’t mean the microscope kind. God is already infinitely great. We cannot make him bigger than he is. We cannot add to his splendor or enhance his worth. He is who he is, unlimited and eternal, the source and sustainer of everything that exists.

Magnifying God is telescope work. It means seeing him more clearly—experiencing him, knowing him better, recognizing him for who he truly is. When we “glorify” God, we’re not inflating his reputation; we’re displaying his character, worth, and greatness so that we and others can see him better.

This is what Paul means when he writes, “Whether you eat or drink, or whatever you do, do all to the glory of God” (1 Corinthians 10:31). Every activity—the mundane and the momentous, the spiritual and the secular—can become an act of glory-giving when we orient it toward God. Work can glorify God. Rest can glorify God. Relationships, creativity, service, suffering—all of it can display something of who God is.

This is purpose with substance. It answers the “so what” question that meaninglessness cannot address. If you were created by an infinite God for the purpose of knowing, enjoying, and displaying his glory, then your existence matters. Every day matters. Every choice matters. You’re not killing time between birth and death; you’re participating in something eternal.

“From him and through him and to him are all things. To him be glory forever. Amen” (Romans 11:36). Everything originates in God, is sustained by God, and exists for God. Purpose is found not by looking inward but upward—not by constructing meaning for yourself but by receiving it from the One who made you.

Why God’s Self-Glory Is Not Narcissism

At this point, an objection naturally arises. If God made us for his glory, isn’t that self-serving? Isn’t a God who demands worship rather egotistical? We’d consider a human being who constantly sought their own glory to be a narcissist. Why is it different with God?

The objection makes sense on the surface, but it misses something crucial.

Consider what God treasures most. If God, the supremely wise Creator, were passionate about something other than himself—if he treasured some creature or creation more than his own being—that would imply that something in the universe is greater than God. It would mean God acknowledges a higher value, a greater treasure, a worthier object of devotion than himself. But nothing is greater than God. For God to treasure anything above himself would be for God to commit idolatry.

Now consider our situation. What do our souls actually need? What will truly satisfy the deepest longings of the human heart? Not money or success or relationships or experiences—we’ve all tasted these and found them unable to fully satisfy. What we ultimately need is God himself. He is, as Augustine famously prayed, the one in whom our restless hearts find rest.

Here’s the crucial insight: the most loving thing God can do for us is to remain faithful to himself. If he pointed us toward anything other than himself as the ultimate source of joy, he would be directing us toward what cannot satisfy. He would be withholding the only thing that can truly fulfill us.

Think of it this way. Imagine a tour guide in a spectacular national park—mountains and waterfalls and vistas that take your breath away. Would you criticize the guide for constantly pointing you toward the scenery? “Stop talking about the canyon! You’re being so self-centered about this canyon!” Of course not. The guide keeps pointing to the canyon because the canyon is genuinely magnificent and because showing you its magnificence is the best gift he can give you.

God is like a tour guide who keeps pointing to himself—not because he’s needy or insecure but because he knows he is what our souls are made for. He’s not withholding himself to toy with us. He’s revealing himself because experiencing his glory is the greatest possible good for us. His passion for his own glory and his love for us are not in tension; they’re the same movement. In glorifying himself, he gives us what we most desperately need.

This is why Jesus could say, “Father, I desire that they also, whom you have given me, may be with me where I am, to see my glory” (John 17:24). What gift does Jesus want most for his people? To see his glory. Not because he’s an egomaniac but because he knows that seeing his glory is their supreme joy, their ultimate satisfaction, their eternal good.

One day, “the earth will be filled with the knowledge of the glory of the Lord as the waters cover the sea” (Habakkuk 2:14). This isn’t bad news. This is the best news possible—a promise that the universe will finally see clearly, that the veil will be lifted, that we will know the One we were made to know.

Why We Lose Passion for God’s Glory

If we were made to glorify God, and if glorifying God is our greatest good, why does it so often feel like a chore? Why do we drift toward self-glory so easily? Why does passion for God’s glory feel like something we have to work up rather than something that flows naturally?

The sermon source identifies eight reasons we struggle to be passionate about God’s glory—eight obstacles that dull our vision and drain our zeal.

An unbalanced schedule. When we’re too busy, we have no margin to reflect on God or enjoy his presence. When we’re too idle, we become self-focused and restless. Neither extreme cultivates passion for God’s glory. We need rhythms of work and rest, engagement and withdrawal, that keep God at the center rather than at the margins.

Unused talents. God has given each of us gifts and abilities. When we neglect them—when we bury what he’s entrusted to us—we lose a primary avenue for experiencing his glory. Using your gifts in service to God and others connects you to purpose. Sitting on them disconnects you.

Unconfessed sin. Guilt is a glory-killer. When sin remains unaddressed, it creates a barrier between us and God, robbing us of joy and making worship feel hypocritical. “If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just to forgive us our sins and to cleanse us from all unrighteousness” (1 John 1:9). The path back to passion runs through confession.

Unresolved conflict. Broken relationships drain our emotional and spiritual energy. When we’re nursing grudges or avoiding reconciliation, we have little capacity left for cultivating passion for God. The horizontal dimension of our lives affects the vertical.

An unsupportive environment. We become like the people we surround ourselves with. If your closest companions are indifferent to God’s glory, their indifference will infect you. We need community that fans the flame rather than dampening it.

Unclear purpose. When we’ve lost sight of why we exist, everything becomes “motion without meaning.” We go through the routines of life—even religious routines—without any sense of what it’s all for. Recovering clarity about purpose re-energizes everything.

An undernourished relationship with God. You cannot maintain passion for someone you never spend time with. Neglecting prayer and Scripture starves the soul. The fire needs fuel, and the fuel is God’s Word and presence.

Not truly knowing him. Perhaps most fundamentally, we lose passion for God’s glory when we have a “Jesus-y” resume but no real relationship with Jesus. We’ve accumulated religious information without personal transformation. We’re satisfied with the gift shop—the trinkets of Christianity—instead of the Giver himself.

These obstacles are not insurmountable. Each one can be addressed. But addressing them requires honesty about where we are and intentionality about where we want to be. Passion for God’s glory doesn’t happen by accident. It’s cultivated.

All of Life for His Glory

Here’s the practical implication of all this: if you were made for God’s glory, then every part of your life is meant to reflect it.

Not just Sunday morning. Not just your “spiritual” activities. All of it. “Whatever you do, do all to the glory of God” (1 Corinthians 10:31). The “whatever” is comprehensive. Your work can glorify God when done with integrity, excellence, and service to others. Your family life can glorify God when marked by love, patience, and sacrifice. Your leisure can glorify God when it refreshes you for continued service rather than pulling you away from him. Your suffering can glorify God when you trust him through it and find him sufficient.

This transforms the ordinary. The teacher grading papers, the nurse changing bandages, the parent making lunches—these aren’t secular activities that merely fund your real purpose elsewhere. They are arenas for glory-giving. They are opportunities to display something of God’s character through your work, your attitude, your relationships.

And this transforms your motivation. You’re not working to prove your worth—that’s already settled in Christ. You’re not serving to earn God’s favor—that’s already secured by grace. You’re working and serving and living as an expression of who you are and who God is. Purpose flows from identity.

Consider how this reframes the Monday morning question. You wake up not to “What do I have to get through today?” but to “How can I display God’s glory today?” The tasks may be the same. The motivation—and therefore the experience—is entirely different.

Our purpose to glorify God doesn’t end when we die. In fact, the ultimate goal is eternal glory with him—seeing him face to face, knowing him fully, dwelling in his presence forever. But what exactly happens when we leave this life? What awaits us on the other side of death? That’s the final question we must answer.

Reflection Questions

-

Consider the two questions: “What do you do?” and “Why do you exist?” How would you answer each one? Does your answer to the second flow naturally from your daily life, or does it feel disconnected from how you actually live?

-

The chapter argues that self-created meaning cannot truly satisfy. Do you agree? Have you experienced this—constructing a purpose that eventually felt hollow?

-

“Magnifying God is telescope work, not microscope work.” How does this distinction change the way you think about worship and living for God’s glory? What would it look like to see God more clearly in your current circumstances?

-

Review the eight obstacles to passion for God’s glory. Which one or two resonate most with your current situation? What concrete step could you take this week to address them?

-

How might your ordinary activities—work, relationships, daily tasks—look different if you approached them as opportunities to display God’s glory rather than just things to get done?

Key Takeaways

-

The question “Why am I here?” is more fundamental than “What do I do?”—it asks about purpose rather than mere activity, and every worldview must offer an answer.

-

Secular meaninglessness cannot satisfy the human soul; neither can the self-focused “be happy” message of Moral Therapeutic Deism—both leave us without substantial purpose.

-

The biblical answer is that we were created for God’s glory (Isaiah 43:7), not to make God bigger but to see and display him more clearly, like a telescope rather than a microscope.

-

God’s passion for his own glory is not narcissism but love—he points us to himself because he knows he alone can satisfy our souls; his glory and our good are the same thing.

-

Purpose applies to all of life: “Whatever you do, do all to the glory of God” (1 Corinthians 10:31)—transforming ordinary activities into opportunities for displaying God’s character.