Who Am I?

Finding identity in being made in God's image and becoming a new creation in Christ, rather than in cultural categories.

The Identity Crisis

A strange epidemic is sweeping through Western society, one that doesn’t show up in blood tests or medical imaging but leaves its marks everywhere.

Anxiety disorders have become the most common mental health issue in America, affecting some 40 million adults. Depression rates have tripled over the past decade among young adults. Teen suicide rates have climbed 60 percent since 2007. Social media feeds overflow with self-help strategies, affirmations, and identity declarations—“I am enough,” “Be your authentic self,” “My truth”—yet the people posting them seem no more settled in who they are than before they typed the words.

Something is deeply wrong. For all our talk about self-discovery and self-expression, we seem more confused about ourselves than ever. The question “Who am I?” has never been more urgent—or more elusive.

Consider the paradox. We live in an era of unprecedented freedom to define ourselves. Previous generations had their identities largely assigned by family, community, religion, and social role. You were a farmer’s son or a merchant’s daughter. Your religion was your parents’ religion. Your social standing was inherited. Today, at least in the West, we’re told we can be anything, choose anything, become anything. The constraints have fallen away. We are free.

And yet this freedom has produced not confidence but crisis. When everything is possible, nothing feels secure. When identity becomes a project rather than a given, we’re left anxiously constructing ourselves from scratch—and the materials keep shifting beneath our feet.

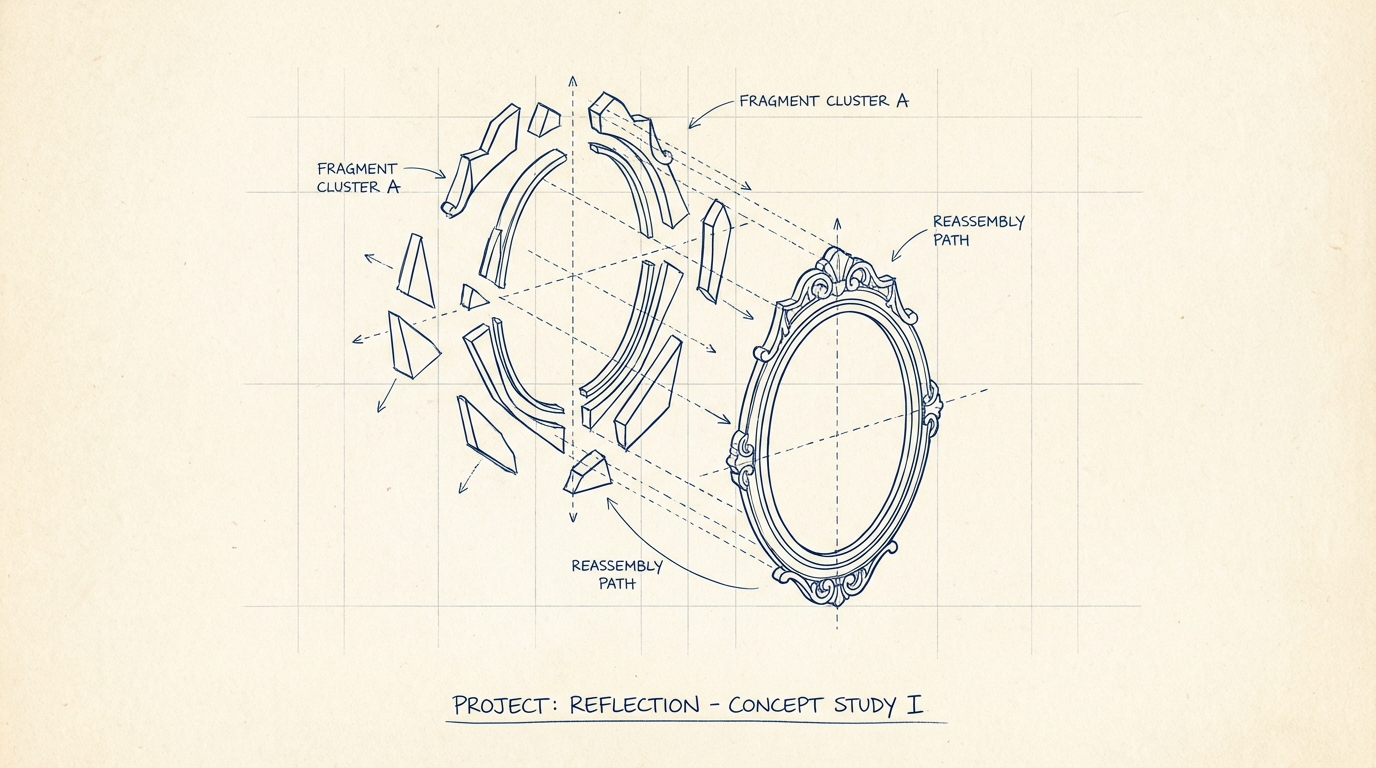

How one answers the question “Who am I?” is fundamentally determined by their underlying worldview. The lens through which you view reality shapes the reflection you see in the mirror. Get the worldview wrong, and you’ll get your identity wrong. Get your identity wrong, and everything that flows from it—your relationships, your purpose, your sense of worth—will be distorted.

Of the eight questions every worldview must answer, identity may be getting more mileage in global conversations right now than any other. This isn’t merely a philosophical curiosity. This is the question keeping teenagers awake at night. This is the question driving adults into therapy. This is the question tearing families and communities apart.

We need an answer that actually works.

The Secular Options

Contemporary culture offers us two primary frameworks for answering the identity question—and neither can bear the weight we’re placing on it.

The Critical Theory Approach

The first framework has emerged from academic critical theory and now saturates much of public discourse. In this view, identity is fundamentally about group membership—specifically, where you land on the spectrum of power. Are you an oppressor or oppressed? Privileged or marginalized? The categories shift depending on which characteristic is being analyzed—race, gender, class, sexuality—but the structure remains constant: humanity is divided into those with power and those without, and your identity is determined by which side of that line you occupy.

This framework has some legitimate concerns at its root. Power imbalances do exist. Injustice is real. Certain groups have historically been marginalized, and calling attention to that isn’t wrong. Christians should be the first to acknowledge that sin has corrupted social structures and that the vulnerable deserve protection.

But as a foundation for identity, this framework collapses under its own weight.

First, it locks people into categories they didn’t choose and can never escape. If your identity is primarily about your group membership and its relationship to power, then the individual disappears. You become a representative of your demographic before you’re a person in your own right. Your experience is assumed based on your category. Your voice matters more or less depending on which box you check. The unique image-bearer God created is flattened into a position on a power grid.

Second, the oppressor/oppressed binary cannot provide the basis for human dignity it claims to protect. Why does oppression matter? Why are human beings worth defending? The framework has no answer. It assumes human dignity while providing no ground for it. If we’re nothing but expressions of power structures, then the strong dominating the weak isn’t wrong—it’s just how reality works. The moment you say oppression is wrong, you’ve appealed to a moral standard outside the framework—but the framework denies such standards exist.

Third, and most personally damaging, this identity structure offers no redemption. If you’re in an oppressor category, you remain guilty regardless of your individual actions. If you’re in an oppressed category, you remain a victim regardless of your individual circumstances. There’s no path to reconciliation, no hope of transformation, no room for people to be more than their demographic. The best you can hope for is power—and power games never end.

The Self-Constructed Approach

The second option is perhaps even more pervasive: identity as personal creation. “Be your authentic self.” “Follow your heart.” “Live your truth.” “Only you can define who you are.”

This sounds liberating. It promises freedom from external constraints, from the expectations of others, from the boxes society tries to put you in. You are the author of your own story, the sculptor of your own identity, the final authority on who you really are.

But consider the burden this places on you.

If identity is self-constructed, then you must create yourself from nothing. You have no given materials to work with, no external reference point, no foundation that doesn’t depend on your own choosing. You must determine your own worth, purpose, and meaning—and somehow generate enough conviction to stake your life on conclusions you know you invented.

And which self should you follow? Today’s self might passionately believe things yesterday’s self rejected and tomorrow’s self will regret. Feelings shift. Desires contradict. The heart that’s supposed to guide you is, as Jeremiah bluntly observed, “deceitful above all things, and desperately sick” (Jeremiah 17:9). Building your identity on your feelings is like building your house on quicksand.

Moreover, self-constructed identity is inherently unstable because it depends entirely on your capacity to maintain it. You must constantly affirm yourself, defend your choices, and project confidence in your self-creation. The moment doubt creeps in—and it will—the whole structure wobbles. No wonder the most “self-assured” generation in history is also the most anxious.

And here’s the deepest problem: if you’re the ultimate authority on who you are, then your identity has no weight beyond your own assertion. It’s like printing your own currency—the bills may look impressive, but they’re backed by nothing.

The Biblical Alternative

Against these unstable foundations, the biblical worldview offers something radically different: identity that is given, not constructed. Identity grounded in what is true about you, not what you feel about yourself. Identity that comes from the One who made you and therefore actually knows who you are.

Created in God’s Image

We explored in Chapter 4 how every human being is made in the image of God—stamped with the divine likeness, reflecting the Creator in unique ways, possessing inherent dignity and worth. This truth establishes the foundation of your identity: you are not an accident of evolution or a cog in a power machine or a product of your own imagination. You are a creature made by God, designed with intention, valued before you did anything to earn it.

Being made in God’s image means you have rational capacity—the ability to think, reason, and recognize truth. It means you have moral capacity—a conscience that acknowledges right and wrong. It means you have relational capacity—you are made for communion with God and others. It means you have creative capacity—like your Maker, you can bring new things into existence.

These capacities aren’t achievements you earned. They’re gifts you received. They define you regardless of how well you exercise them. The infant in the womb, the person with profound cognitive disability, the prisoner on death row—all bear this image. All possess this dignity. All are known and valued by their Creator.

Here, then, is the first pillar of biblical identity: you are a creature of God, made in his image, possessing sacred worth that nothing can revoke.

New Creation in Christ

But Chapter 5 showed us that something went terribly wrong. Our first parents rejected their Creator, and the human race fell under a curse. The image of God wasn’t destroyed, but it was defaced. Our capacities remained, but they were corrupted. We still bear God’s likeness, but we bear it as broken mirrors—recognizable, yet shattered.

And Chapter 6 revealed God’s solution. Jesus, the second Adam, accomplished what the first Adam failed to do. He lived the life we should have lived and died the death we deserved to die. Through faith in him, we are forgiven, reconciled, and—here’s the key word—re-created.

“Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation. The old has passed away; behold, the new has come” (2 Corinthians 5:17).

This is identity transformation at the deepest possible level. You are not merely forgiven for what you’ve done. You are made new in who you are. The “old self” with its corrupted desires and distorted identity has been put to death in Christ. A “new self” has emerged—still you, but renewed, restored, realigned with your Creator’s intentions.

Paul puts it starkly: “I have been crucified with Christ. It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me. And the life I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me” (Galatians 2:20). The old identity died with Christ. The new identity was raised with him.

Consider what this means. Your identity is no longer rooted in your performance—you don’t have to earn your way to worth. Your identity is no longer dependent on your past—the old has passed away. Your identity is no longer contingent on others’ opinions—what God says about you outweighs any human verdict.

In Christ, you are chosen. “He chose us in him before the foundation of the world” (Ephesians 1:4). Before you existed, God set his love on you. You weren’t selected for your potential or your virtue but simply because it pleased him to choose you.

In Christ, you are adopted. “He predestined us for adoption to himself as sons through Jesus Christ” (Ephesians 1:5). You’re not a servant hoping to stay in good standing. You’re a child of the King, welcomed into the family with full inheritance rights.

In Christ, you are redeemed. “In him we have redemption through his blood, the forgiveness of our trespasses” (Ephesians 1:7). The price has been paid. The debt is cancelled. You belong to the One who bought you with his own life.

In Christ, you are sealed. “You were sealed with the promised Holy Spirit” (Ephesians 1:13). Your new identity isn’t probationary. The Spirit himself marks you as God’s permanent possession.

“See what kind of love the Father has given to us, that we should be called children of God; and so we are” (1 John 3:1). Note John’s emphasis: “and so we are.” This isn’t wishful thinking or positive self-talk. This is reality. If you are in Christ, you are a child of God. The statement is true whether you feel it or not.

Peter pulls all these threads together: “But you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for his own possession, that you may proclaim the excellencies of him who called you out of darkness into his marvelous light” (1 Peter 2:9). Chosen. Royal. Holy. Possessed by God himself. This is who you are.

Living From Identity, Not For Identity

Here is perhaps the most practical implication of biblical identity: you live from your identity in Christ, not for your identity.

The secular alternatives leave you constantly working to establish, prove, and protect your identity. You must achieve to feel valuable. You must perform to maintain worth. You must craft and curate the self you present to the world, anxiously hoping others will validate your existence. Identity becomes something you’re always chasing, never catching—a carrot perpetually dangling just out of reach.

The gospel reverses this exhausting pattern. Because your identity is secure in Christ, you no longer need to prove anything. You can stop trying to earn what has already been given. You can rest in who you are and then work from that rest.

Think of the difference this makes. When your identity depends on your career, job loss devastates you. When your identity is in Christ, job loss is painful but not identity-shattering—you’re still a beloved child of God. When your identity depends on others’ approval, criticism destroys you. When your identity is in Christ, criticism stings but doesn’t define you—God’s verdict outweighs every human opinion. When your identity depends on your performance, failure is catastrophic. When your identity is in Christ, failure is an opportunity for grace—your worth was never on the line.

This is what it means to live from identity rather than for it. You don’t wake up each morning needing to construct yourself from scratch. You wake up already knowing who you are. You’re not building your identity through your activities; you’re expressing your identity through them.

Consider how this reframes everyday life. Work becomes an expression of your identity as a creative image-bearer, not a desperate attempt to establish your worth. Relationships become opportunities to love from fullness rather than need from emptiness. Service becomes overflow rather than compensation. Even suffering takes on new meaning—you can endure trials that threaten your circumstances because they can’t threaten your identity.

When We Forget Who We Are

This doesn’t mean Christians never struggle with identity. We do. The reality of our new identity in Christ can feel distant on Monday morning when the bills pile up and the criticism stings and the old patterns reassert themselves.

The New Testament writers knew this, which is why they spent so much ink reminding believers who they already were. Paul didn’t write Ephesians 1 to uncertain seekers but to baptized believers who apparently needed to hear again that they were chosen, adopted, and sealed. We are, all of us, forgetful creatures.

Several things make us forget our true identity.

Sometimes we forget because we’re listening to the wrong voices. The world, the flesh, and the enemy all have opinions about who we are—and none of them match what God says. The world tells us our identity is what we achieve, accumulate, or attract. The flesh tells us our identity is our desires and impulses. The enemy tells us our identity is our failures and sins. When we listen to these voices instead of God’s Word, our sense of identity drifts.

Sometimes we forget because we’re depending on feelings rather than truth. Faith isn’t about manufacturing emotions; it’s about trusting what is true regardless of how we feel. On days when you don’t feel like a beloved child of God, you still are one. The truth doesn’t change because your mood does.

Sometimes we forget because we’re more focused on what we do than on what Christ has done. Performance-based identity is the default setting of the human heart, and we constantly slip back into it. We must deliberately preach the gospel to ourselves: “My acceptance doesn’t depend on today’s performance. Christ’s finished work is my only hope.”

Sometimes we forget because we’re isolated from community. The Christian faith is not meant to be lived alone. We need brothers and sisters who remind us of our identity when we’ve lost sight of it—who speak truth when we believe lies, who point us back to Christ when we’ve wandered into self.

The solution to identity amnesia isn’t trying harder to feel secure. It’s returning again and again to what God has declared true about you in Christ. It’s saturating your mind with Scripture until the truth of who you are becomes more real than the lies you’re tempted to believe. It’s gathering with God’s people who reinforce your true identity. It’s remembering that you are not defined by your past, your performance, or others’ opinions—you are defined by the God who made you and the Christ who redeemed you.

You Are Not Your Own

There is one more dimension of biblical identity that distinguishes it from every secular alternative: you belong to someone.

“You are not your own, for you were bought with a price” (1 Corinthians 6:19-20). The self-constructed approach insists that you belong only to yourself. The biblical worldview says you belong to Christ.

This might sound like bad news—a loss of autonomy, a surrendering of freedom. But here’s what the self-constructed approach can never tell you: belonging is actually what you were made for. Autonomy is not the highest human good. Being known, loved, and owned by the One who designed you—that is what your soul craves beneath all its posturing about independence.

To belong to Christ is not slavery but homecoming. The restless search for identity ends when you realize you were never meant to create yourself. You were meant to be found.

Knowing who we are naturally leads to asking why we’re here. Identity and purpose are intimately connected. If we’re image-bearers and new creations, if we belong to the God who made and redeemed us, then surely our lives are meant for something. We weren’t created merely to exist but to express something—to do something with this identity we’ve been given.

What is our purpose? That’s the question we’ll explore next.

Reflection Questions

-

The chapter describes two secular approaches to identity: Critical Theory (group membership/power) and self-construction (“be your authentic self”). Which of these has more influence on how you tend to think about your own identity? How has that influenced you?

-

Read 2 Corinthians 5:17 and Galatians 2:20. What does it mean practically that the “old has passed away” and “it is no longer I who live”? How would your life look different if you lived more fully from this truth?

-

Consider the distinction between living from identity versus for identity. In what areas of your life are you still trying to earn or prove your worth rather than resting in what God has already declared true about you?

-

What voices most often cause you to forget your identity in Christ? The world’s messages about achievement? Others’ opinions? Your own sense of failure? How might you more intentionally counter those voices with biblical truth?

-

“You are not your own, for you were bought with a price.” Does belonging to Christ feel like freedom or restriction to you? What would it mean to experience this belonging as “homecoming”?

Key Takeaways

-

The modern identity crisis stems from worldviews that either reduce identity to group membership (Critical Theory) or place the impossible burden of self-construction on individuals—neither can provide the stable foundation we need.

-

Biblical identity begins with being made in God’s image (inherent worth) and is transformed through faith in Christ, who makes us “new creations”—chosen, adopted, redeemed, and sealed.

-

Scripture declares our identity in Christ with language of fact, not feeling: we are children of God, we are a royal priesthood—whether we feel it or not.

-

Christians are called to live from their identity in Christ rather than for their identity—working from rest rather than toward it, secure in what has already been given rather than anxious about what must be earned.

-

True identity is found not in autonomy but in belonging—being known, loved, and owned by the God who made us is the homecoming our souls were created for.