What's Wrong with the World?

The biblical diagnosis of sin as the root problem, federal headship, and the first glimmer of hope in the protoevangelium.

“I Am”

In the early twentieth century, The Times of London reportedly asked a number of prominent authors to write essays responding to the question: “What’s wrong with the world?”

The Catholic writer G.K. Chesterton submitted the shortest reply:

Dear Sirs,

I am.

Yours, G.K. Chesterton

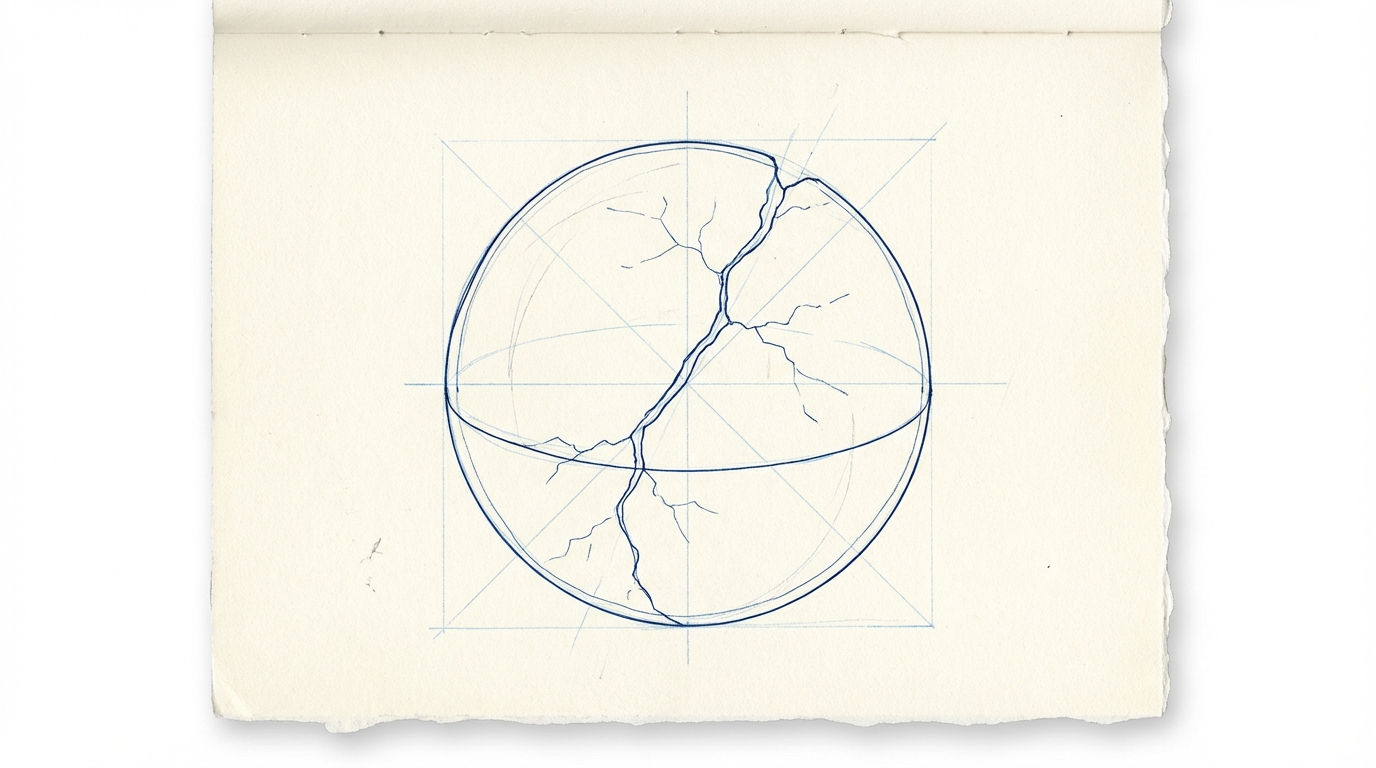

Whether the anecdote is apocryphal or not, it captures something essential. When we survey the wreckage of human history—the wars, the oppression, the cruelty, the betrayal—we instinctively look outward for explanations. The problem must be them. The powerful. The ignorant. The system. The other tribe.

Chesterton’s answer is jarring because it points the finger inward. The diagnosis of what ails the world must begin in the mirror.

We established in the previous chapter that God created everything good. He spoke the cosmos into existence through his Word, calibrated the universal constants to permit life, encoded the language of DNA into every cell, and crowned his creation with human beings made in his own image—declared “very good.”

But look around. Does the world appear “very good” to you?

A mother buries her child. A tyrant starves his people. A spouse discovers infidelity. A promising career is destroyed by addiction. Children are trafficked. Nations are ravaged. And even in the quieter corners of ordinary life, we encounter pettiness, selfishness, anxiety, and grief. Something has gone catastrophically wrong.

Every worldview must account for this. Every framework for understanding reality must explain the gap between how things ought to be and how things are. The answers we give reveal more about our worldview than almost anything else.

What is wrong with the world?

The Answers That Miss the Mark

Different worldviews offer different diagnoses.

Moral Therapeutic Deism—that soft, therapeutic spirituality that has infected much of contemporary Christianity—locates the problem in unhappiness. What’s wrong is that people aren’t feeling good about themselves. The solution is more self-esteem, more positive thinking, more affirmation of our essential goodness. The problem is outside us: circumstances, negativity, insufficiently supportive environments. If we could just adjust the external conditions and nurture our inner potential, everything would work out.

Marxism and its ideological offspring locate the problem in systemic injustice. What’s wrong is that oppressive power structures disadvantage certain groups. The solution is to overthrow these structures, redistribute power, and reorganize society along egalitarian lines. The problem is the system—capitalism, patriarchy, colonialism—and the oppressors who benefit from it. Change the structures, and you change humanity.

Secular humanism locates the problem in unsolved problems. What’s wrong is that we haven’t yet applied sufficient reason and science to our challenges. Climate change, disease, poverty—these are technical problems awaiting technical solutions. The problem is insufficient knowledge and technology. Advance education, fund research, develop better systems, and human flourishing will follow.

Each of these diagnoses contains a grain of truth. Unhappiness is real. Injustice is real. Unsolved problems are real. But notice what they share in common: they all identify the problem as fundamentally external to the human heart. The ailment is out there—in circumstances, systems, or ignorance—not in here.

This is why these solutions consistently fail. We’ve had centuries of educational advancement, technological progress, and political revolution. We’ve reorganized societies, redistributed wealth, and reimagined institutions. Yet the fundamental problems persist. New oppressors replace old ones. New forms of cruelty emerge. The well-educated prove as capable of evil as the ignorant. The rich suffer despair alongside the poor.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn, who spent years in the Soviet gulag, saw through the ideology that claimed to create utopia through systemic change:

The line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either—but right through every human heart.

The biblical worldview agrees. The symptoms are external, but the disease is internal. What’s wrong with the world is the problem of the human heart—and that problem has a name.

Sin.

Defining the Disease

We need to be careful here. “Sin” has become a word that modern ears easily dismiss. It sounds archaic, religious, judgmental. When contemporary people hear “sin,” they picture rule-breaking—violating arbitrary religious prohibitions about what you can eat or drink or do on Sundays. Sin sounds like the complaint of uptight people who can’t handle others having a good time.

But the biblical concept is far more serious and far more personal.

The Hebrew word most commonly translated “sin” (chata) means to miss the mark—like an archer whose arrow falls short of the target. The Greek equivalent (hamartia) carries the same sense. Sin isn’t primarily about breaking rules; it’s about failing to hit the target for which we were made.

What is that target? The glory of God. We were created to know God, love God, reflect God, and honor God with our lives. Sin is the comprehensive failure to do so. It’s not just bad actions; it’s the underlying disposition that produces them—a heart curved inward on itself rather than oriented outward toward God and others.

But there’s more. Sin is not merely falling short. The Genesis narrative presents it as deliberate rebellion.

God created Adam and Eve in perfect relationship with himself. He placed them in a garden of abundance, giving them meaningful work and intimate communion. He imposed only one restriction: “Of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall surely die” (Genesis 2:17).

This was not arbitrary rule-making. God was establishing something profound—a covenant. A covenant is different from a contract. Contracts are transactional: I do X, you do Y, and we both benefit. Covenants are relational: they create bonds of loyalty, trust, and mutual commitment that transcend mere transaction. God wasn’t making a deal with Adam. He was inviting him into relationship.

The tree represented something essential: the acknowledgment that God alone defines good and evil. By honoring the boundary, Adam would affirm that he was the creature and God was the Creator, that he would receive the definition of reality from God rather than seizing it for himself.

The serpent’s temptation targeted exactly this: “You will be like God, knowing good and evil” (Genesis 3:5). The promise was autonomy—the ability to define reality for yourself, independent of God’s word. The temptation was to become your own god.

Adam chose rebellion.

The Representative Head

This is where the story becomes simultaneously more challenging and more important. Adam’s choice didn’t affect only Adam. It affected everyone.

The Bible introduces a concept that modern Western individualism struggles to grasp: federal headship. The term comes from foedus, the Latin word for covenant. A federal head is a representative whose actions count for those he represents.

We actually understand this better than we might think. When the president of a nation signs a treaty, every citizen becomes bound by it—even those who voted against the president, even those who weren’t yet born when the treaty was signed. The representative’s action counts for the represented.

Consider Pearl Harbor. On December 7, 1941, Japan attacked American naval forces in Hawaii. American civilians sleeping peacefully in Kansas woke up to discover they were at war. They hadn’t voted for war. They hadn’t fired any weapons. They hadn’t personally offended Japan. Yet the actions of their national leaders had placed them in a state of conflict they didn’t individually choose.

Adam was humanity’s federal head. God appointed him as the representative of the entire human race. His covenant with God was a covenant on behalf of all his descendants. Whatever Adam did would be credited to everyone he represented.

“As Adam goes,” the pastor put it, “so we all go.”

This means Adam’s rebellion was not merely personal. It was representational. When Adam broke the covenant, humanity broke the covenant. When Adam fell, humanity fell. His choice to seize autonomy from God—to become his own arbiter of good and evil—became charged to his account and to ours.

The apostle Paul states it plainly: “Sin came into the world through one man, and death through sin, and so death spread to all men because all sinned” (Romans 5:12). And again: “For as in Adam all die, so also in Christ shall all be made alive” (1 Corinthians 15:22).

”But That’s Not Fair!”

I can hear the objection already. How can we be held accountable for someone else’s choice? We weren’t there. We didn’t eat the fruit. Why should we suffer for what Adam did thousands of years before we were born?

The objection seems intuitively compelling—until we examine it more carefully.

First, a distinction: we are affected by Adam’s choice, but we are not responsible for it. There’s a difference between being guilty of Adam’s specific act (we’re not) and being caught up in the consequences of his act (we are). No one is condemned for Adam’s personal sin. We’re condemned for our own sin—but we sin because we inherited a corrupted nature from our federal head.

Think of it this way. If your ancestor contracted a genetic disease, you might inherit that disease. You didn’t choose it. You didn’t deserve it. Yet it’s yours. Adam transmitted not just physical DNA but spiritual DNA—a disposition toward rebellion, a heart curved in on itself, a nature that prefers autonomy to submission.

Second, notice that our objection assumes something significant: that representation is inherently unfair. But is it? We don’t object when representation works in our favor. We’re quite happy for someone to win a war on our behalf, sign a beneficial treaty on our behalf, or earn money that benefits our family. Representation only seems unjust when the representative fails.

But here’s what’s remarkable: the same principle of federal headship that condemns us in Adam is the principle that saves us in Christ. If you reject the idea of representation, you lose not only the problem but also the solution. The good news depends on another Representative whose actions count for those he represents.

We’ll explore that fully in the next chapter. For now, recognize that federal headship isn’t an arbitrary imposition; it’s the architecture of redemption.

Third, let’s be honest: if you had been in the garden, would you have done differently? The whole of human history is an extended answer to that question. Given perfect conditions, humanity consistently chooses rebellion. Every nation, every culture, every individual confirms the pattern. We aren’t innocent bystanders corrupted by Adam’s mistake; we’re eager participants who prove daily that the disease is real.

The Consequences Unleashed

When Adam chose rebellion, consequences cascaded through creation.

The immediate effects are recorded in Genesis 3. Shame: “They knew that they were naked” (v. 7)—awareness of exposure, vulnerability, inadequacy. Fear: “I was afraid” (v. 10)—the instinctive recoil from the holy God they had defied. Hiding: “They hid themselves from the presence of the LORD” (v. 8)—the futile attempt to escape the gaze of the One who sees all. Blame: “The woman whom you gave to be with me, she gave me fruit” (v. 12)—the reflexive deflection of responsibility that has characterized human relationships ever since.

Then came the curses.

To the serpent: eternal enmity and ultimate defeat. To the woman: pain in childbearing and struggle in the marital relationship. To the man: frustrating toil, a ground that produces thorns instead of easy abundance, and eventual death—“for you are dust, and to dust you shall return” (v. 19).

The curses touch everything. Work becomes toilsome. Relationships become strained. The body decays. The earth resists our efforts. And hovering over it all is death—the final enemy, the wage of sin, the return to dust that awaits every descendant of Adam.

This is why the world doesn’t look “very good.” The corruption spread from the human heart outward to every domain of existence. Paul says that “the whole creation has been groaning together in the pains of childbirth until now” (Romans 8:22). The groaning of a woman in labor, the groaning of the land under drought, the groaning of the human heart under grief—all of it traces back to that moment in the garden when the federal head of humanity chose autonomy over trust.

The First Glimmer of Hope

But here is where the story takes an unexpected turn.

In the very moment of pronouncing the curse, God speaks a promise. Embedded in the judgment is a prophecy. To the serpent, God declares:

I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and her offspring; he shall bruise your head, and you shall bruise his heel. (Genesis 3:15)

Theologians call this the protoevangelium—the “first gospel.” It’s the earliest announcement of redemption, hidden in the curse like a seed waiting to germinate.

Notice the details. First, there will be conflict—ongoing enmity between the serpent’s offspring and the woman’s offspring. The war that began in the garden will continue through history.

Second, the deliverer will come through the woman’s line, not Adam’s. “Her offspring” is an unusual phrase; biblical genealogies typically trace through the father. This peculiar wording hints at something: the coming savior will be born of woman but will not be under Adam’s federal headship in the ordinary way.

Third, the outcome of the conflict is already determined. The serpent will strike the deliverer’s heel—a painful but non-lethal blow. But the deliverer will crush the serpent’s head—a decisive, lethal blow. The serpent will wound; the offspring will destroy.

Isaiah would later clarify: “Behold, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and shall call his name Immanuel” (Isaiah 7:14). A virgin. Not the normal course of human reproduction. A child who would be “God with us,” born of woman but not generated by Adam’s corrupted line.

From the moment of the fall, God was planning the rescue. Before Adam and Eve even left the garden, a promise of redemption was spoken. The curse would be lifted. The serpent would be crushed. Humanity’s federal head had failed, but another Head was coming—one who would succeed where Adam failed, who would undo the curse that Adam brought.

The diagnosis is devastating: the problem is the human heart, corrupted from our first representative and confirmed by our own choices every day. But the diagnosis comes with a prescription—a Deliverer from outside the cursed line, an offspring of woman, a Head who will represent his people not to condemnation but to life.

What does this mean? How does this deliverer accomplish what Adam couldn’t? That’s where we turn next.

Reflection Questions

-

Chesterton’s answer—“I am”—points the finger inward. How do you typically answer the question “What’s wrong with the world?” Do you tend to locate the problem externally (systems, circumstances, other people) or internally?

-

The concept of federal headship says that Adam’s choice counted for all humanity. Does this seem unjust to you? How does understanding that salvation works by the same principle (Christ as our representative) change your evaluation?

-

Genesis 3 describes immediate consequences of the fall: shame, fear, hiding, and blame. Where do you see these patterns operating in your own life and relationships today?

-

The chapter distinguishes being “affected” by Adam’s sin from being “responsible” for it. Does this distinction help address the apparent unfairness of original sin? Why or why not?

-

The protoevangelium (Genesis 3:15) promises a deliverer from the woman’s line who will crush the serpent’s head. How does knowing that God announced redemption at the moment of the fall affect how you view God’s character?

Key Takeaways

-

The fundamental problem with the world is not external (circumstances, systems, ignorance) but internal—the human heart corrupted by sin.

-

Sin is more than rule-breaking; it is missing the mark of God’s glory, failing to be what we were created to be, and deliberate rebellion against God’s rightful authority.

-

Adam served as humanity’s federal head—a representative whose covenant-breaking in the garden affected all his descendants, transmitting a corrupted nature to every human being.

-

We are affected by Adam’s sin (we inherit a sinful nature) though not responsible for his specific act; we confirm the diagnosis through our own daily choices.

-

Even in the curse, God announced hope: the protoevangelium (Genesis 3:15) promised a deliverer from the woman’s line who would crush the serpent’s head—the first hint of redemption that would be fulfilled in Christ.