Is There a God?

The cosmological argument for God's existence and what the cause of the universe must be like.

The Question Science Can’t Answer

Why is there something rather than nothing?

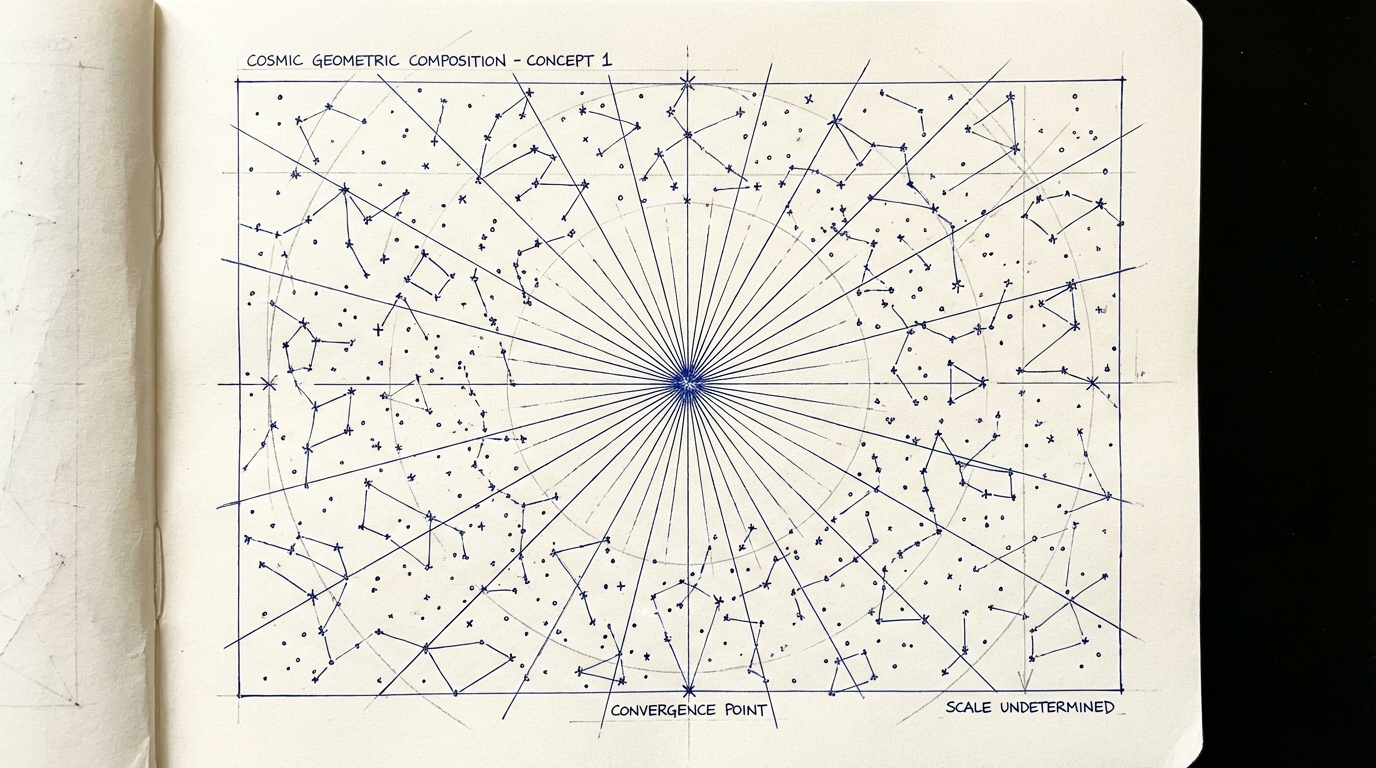

It’s a question that haunts us in unexpected moments—standing beneath a night sky crowded with stars, holding a newborn child, or simply pausing long enough for the noise of daily life to fade. In that silence, the question surfaces: Why is any of this here at all?

Science has made staggering progress explaining how things work. We understand gravitational forces, chemical reactions, biological processes. We can trace the expansion of the universe backward through time, catalog the elements formed in stellar furnaces, map the genetic code that builds a human being from a single cell. But science operates within the framework of what exists. It examines the furniture; it doesn’t explain the room.

The question why there is something rather than nothing steps outside the scientific method. You can’t run an experiment on the absence of everything. You can’t measure nothing or repeat its conditions in a laboratory. The question isn’t unscientific—it’s pre-scientific. It asks about the ground on which all scientific investigation stands.

Every worldview must answer this question, whether explicitly or by implication. The naturalist says the universe simply exists as a brute fact, requiring no explanation. The pantheist says everything is God, so the question dissolves. The biblical worldview says something—Someone—has always existed, uncaused and eternal, and from that Someone everything else proceeds.

But can this claim survive rational scrutiny? Is belief in God a relic of prescientific thinking, or is it the most reasonable explanation for the existence of anything at all?

In the previous chapter, we examined the reliability of Scripture—the manuscript evidence, archaeological confirmation, eyewitness testimony, and prophetic fulfillment that establish the Bible as a trustworthy historical document. Now we turn to Scripture’s central claim: that God exists and is the source of all reality. We’ll approach this claim not with blind faith but with careful reasoning, examining one of the most powerful philosophical arguments for God’s existence.

The argument is ancient, formulated by thinkers across cultures and centuries, refined through generations of philosophical debate. It’s called the cosmological argument, and it begins with a simple observation: things that come into existence have causes.

The Cosmological Argument

The logic of the cosmological argument can be stated in three premises:

Premise 1: Everything that begins to exist has a cause.

This principle seems almost too obvious to state. We observe it constantly. Books don’t appear on shelves spontaneously. Babies don’t materialize from thin air. Buildings require builders, paintings require painters, and even the simplest object has an explanation for its existence. The idea that something could pop into being from literally nothing—not from prior matter, not from fluctuating energy, not from any existing thing—violates our deepest intuitions about reality.

Some skeptics appeal to quantum physics, claiming that particles appear spontaneously from quantum vacuums. But a quantum vacuum isn’t “nothing”—it’s a rich field of fluctuating energy governed by physical laws. The particles that emerge from it have causes within that system. True philosophical nothing—the absence of any being, property, or potentiality whatsoever—has no power to produce anything. As the ancient philosophers recognized, ex nihilo nihil fit: from nothing, nothing comes.

This premise isn’t just an intuition. It’s the foundation of all scientific investigation. Science operates on the assumption that effects have causes, that phenomena can be explained by prior conditions. Abandon this premise, and science itself collapses. If things could simply pop into existence uncaused, then any explanation for anything would be arbitrary. The very rationality we bring to investigating the universe presupposes that the universe operates according to causal principles.

Premise 2: The universe began to exist.

This was a philosophical claim for centuries, but in the twentieth century, it became a scientific one as well.

For most of human history, the dominant scientific assumption was that the universe was eternal. It had always existed; it would always exist. This seemed to eliminate the need for a Creator—if the universe never began, it never needed a beginning cause.

But that assumption has collapsed under the weight of evidence.

First, consider the expansion of the universe. In 1929, astronomer Edwin Hubble observed that distant galaxies are moving away from us, and the farther away they are, the faster they’re receding. The universe is expanding like a balloon being inflated. Run the expansion backward, and everything converges toward a single point—a beginning.

This discovery gave rise to what we now call the Big Bang theory: the idea that the universe began approximately 13.8 billion years ago in an initial singularity of unimaginable density and temperature, from which all matter, energy, space, and time emerged. Before this event, there was no “before”—time itself came into existence with the universe.

Second, consider the Second Law of Thermodynamics. This fundamental principle states that usable energy in a closed system is always decreasing. Left to itself, the universe tends toward disorder and equilibrium. But if the universe were infinitely old, it would have reached maximum entropy already—all energy evenly distributed, no heat differentials, no work possible, no life. The fact that stars are still burning, galaxies are still forming, and you are still reading this sentence means the universe hasn’t been running forever. It had a beginning.

Third, consider the impossibility of traversing an actual infinite. If the past were infinite—if an actually infinite number of moments had elapsed before today—then today could never arrive. You can’t traverse an infinite number of points to reach any destination. But today has arrived. Therefore, the series of past moments is finite. The universe began.

The convergence of philosophical reasoning and scientific discovery points in the same direction: the universe is not eternal. It came into being.

Conclusion: Therefore, the universe has a cause.

If everything that begins to exist has a cause, and the universe began to exist, then the universe has a cause. Something—or Someone—brought reality into being.

But what can we know about this cause?

What the Cause Must Be Like

The argument doesn’t stop with the bare conclusion that the universe has a cause. We can reason further about what characteristics this cause must possess.

Transcendent. The cause of the universe must exist outside the universe—outside the entire time-space-matter continuum. If the cause were part of the universe, it couldn’t have caused the universe to exist. It would need its own explanation. The cause must be transcendent, operating beyond the physical reality we inhabit.

Supernatural. By definition, the cause cannot be governed by natural laws, because natural laws are features of the universe. They came into existence with the universe. Whatever brought the universe into being must operate beyond natural law—that is, supernaturally. This doesn’t mean the cause is irrational or chaotic; it means the cause established the order we observe rather than being subject to it.

Eternal. If the cause of the universe began to exist, it too would require a cause, and we’d have an infinite regress of causes—which we’ve already seen is impossible. The chain of causation must terminate in something that never began, something that exists necessarily and eternally. The cause of the universe must be uncaused itself.

Boundless and Limitless. A cause powerful enough to bring the entire universe into existence—all matter, all energy, all the vastness of cosmic reality—cannot be a limited being. The cause must possess power and knowledge beyond anything we can comprehend, sufficient to generate and sustain everything that exists.

Immaterial. Since the cause brought all matter into existence, the cause itself cannot be material. Before the universe existed, there was no matter. The cause must be non-physical, spiritual in nature.

Personal. Here the argument reaches a crucial juncture. A cause that exists eternally, timelessly, and necessarily, yet produces an effect that begins at a particular moment—how is this possible? An impersonal force that exists eternally would produce its effects eternally. But the universe isn’t eternal; it began. The only way an eternal cause can produce a temporally finite effect is through an act of will—a free decision to create. The cause of the universe must be a personal agent capable of choosing to bring something new into existence.

Consider the characteristics we’ve derived: transcendent, supernatural, eternal, boundless, immaterial, personal. This isn’t a vague philosophical abstraction. This is a description that matches precisely what Scripture reveals about God.

This Matches the Biblical God

“In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth” (Genesis 1:1).

The Bible opens with a claim that anticipates everything the cosmological argument demonstrates. God exists before and beyond creation. God is not part of the natural order but its source. God spoke, and the universe came into being.

The psalmist declares: “Before the mountains were brought forth, or ever you had formed the earth and the world, from everlasting to everlasting you are God” (Psalm 90:2). God’s existence has no beginning and no end. He is the eternal one, the uncaused cause, the ground of all reality.

Paul, addressing Greek philosophers in Athens, proclaimed: “The God who made the world and everything in it, being Lord of heaven and earth, does not live in temples made by man, nor is he served by human hands, as though he needed anything, since he himself gives to all mankind life and breath and everything” (Acts 17:24-25). God is transcendent, needing nothing, sustaining everything.

And John opens his Gospel with breathtaking theology: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things were made through him, and without him was not any thing made that was made” (John 1:1-3). The eternal Word—later identified as Jesus Christ—is the agent of all creation.

The cosmological argument doesn’t prove the God of the Bible specifically; it demonstrates that the universe requires a transcendent, eternal, personal Creator. But this is precisely the God Scripture describes. The philosophical conclusion and the biblical revelation converge on the same reality.

Paul makes this connection explicit: “For what can be known about God is plain to them, because God has shown it to them. For his invisible attributes, namely, his eternal power and divine nature, have been clearly perceived, ever since the creation of the world, in the things that have been made” (Romans 1:19-20). Creation itself testifies to its Creator. The heavens declare the glory of God—not through arbitrary interpretation but through evidence that reasoning minds can perceive.

We’re not manufacturing faith from philosophical speculation. We’re finding that careful reason leads us toward the same God who has revealed Himself in Scripture and in the person of Jesus Christ.

Addressing the Objection

At this point, someone invariably asks: “But who made God?”

It’s a fair question, and it deserves a thoughtful answer rather than dismissal.

The cosmological argument does not claim that everything has a cause. It claims that everything which begins to exist has a cause. That’s a crucial qualification. The argument acknowledges from the start that an infinite regress of causes is impossible—which means the chain of causation must terminate in something uncaused, something that never began to exist.

The question “Who made God?” misunderstands the nature of the argument. We’re not claiming that God is just another link in the chain, requiring His own prior cause. We’re claiming that God is the terminus of the chain—the uncaused first cause, the eternal ground of all reality.

Is this special pleading? Not at all. Everyone who reflects on the existence of the universe must posit something eternal and uncaused—some brute reality that explains everything else without itself requiring explanation. The atheist says this brute reality is the universe itself (or perhaps the multiverse, or quantum fields). The theist says it’s God.

But here’s where the cosmological argument makes progress. We’ve seen strong reasons—philosophical and scientific—for believing that the universe began to exist. The universe isn’t a good candidate for the eternal, uncaused foundation of reality. It has all the marks of a contingent thing: a beginning, an ongoing dependence on physical laws, a trajectory toward entropy. It looks like something that was made, not something that simply is.

God, by contrast, possesses the characteristics required of an ultimate explanation: eternality, necessity, self-existence. As Hebrews puts it, He is the one “who was and is and is to come” (Revelation 4:8). He doesn’t exist by the permission of anything else. He simply is—the great “I AM” who revealed Himself to Moses at the burning bush (Exodus 3:14).

The question isn’t whether something has always existed—something must have. The question is what that something is. The evidence from philosophy, from science, and from our deepest intuitions about causation points not toward mindless matter but toward a personal Creator: transcendent, eternal, powerful, and free.

Why This Matters

This isn’t merely a philosophical puzzle. The existence of God is the most consequential question any human being can face.

If God exists—if the universe was created by a personal, intelligent, purposeful Being—then everything changes. Human existence isn’t a cosmic accident. Moral values aren’t arbitrary social constructions. The longing we feel for meaning, beauty, and justice isn’t evolutionary noise; it’s a signal pointing toward the Source.

If God exists, then He might have something to say about how we should live. He might have purposes we’re meant to fulfill. He might even desire relationship with the creatures He made. The questions that haunt us in the quiet moments—“Why am I here? Does my life matter? Is there hope beyond death?”—become answerable questions with real answers.

The author of Hebrews states it plainly: “Whoever would draw near to God must believe that he exists and that he rewards those who seek him” (Hebrews 11:6). Faith in God’s existence is the foundation for everything else—for seeking Him, knowing Him, and finding in Him the purpose our souls crave.

The cosmological argument doesn’t compel belief. Arguments rarely do. But it removes the excuse that faith is irrational. Believing in an eternal, personal Creator is not a leap into darkness; it’s the most reasonable response to the evidence of our own existence. The universe shouts that it came from somewhere—from Someone. We are not accidents, and neither is the world we inhabit.

If God exists and is the uncaused cause of everything, then He is also the Creator—the One who brought not just matter and energy into being but life, consciousness, and the intricate order we see at every level of reality. But how did creation happen, and what does it tell us about our own origins and value? That’s where we turn next.

Reflection Questions

-

Before examining the cosmological argument, how did you think about the question “Why is there something rather than nothing?” Has your perspective shifted at all?

-

Which premise of the cosmological argument do you find most persuasive? Which, if any, raises questions for you?

-

How do you respond to the “Who made God?” objection? Can you think of other ways to explain why this question misunderstands the argument?

-

Consider the characteristics the cause of the universe must possess (transcendent, eternal, personal, etc.). Does this description challenge or confirm your existing conception of God?

-

If God exists as the eternal Creator, what implications does this have for how you understand your own existence and purpose?

Key Takeaways

-

The question “Why is there something rather than nothing?” lies beyond the reach of science, but every worldview must answer it—the biblical worldview claims an eternal, personal God is the source of all reality.

-

The cosmological argument proceeds in three steps: everything that begins to exist has a cause; the universe began to exist (supported by cosmic expansion, thermodynamics, and the impossibility of traversing an actual infinite); therefore, the universe has a cause.

-

Reasoning about what this cause must be like yields characteristics—transcendent, supernatural, eternal, boundless, immaterial, and personal—that match precisely what Scripture reveals about God.

-

The objection “Who made God?” misunderstands the argument. Something eternal and uncaused must exist; the question is whether the universe or a personal Creator better fits that description.

-

Believing in God is not a leap into irrationality but the most reasonable response to the existence of the cosmos. This belief has profound implications for meaning, purpose, and the possibility of relationship with our Creator.