The Lens Through Which You See Everything

Understanding how worldviews form, operate invisibly, and shape what we perceive—and how transformation happens through the renewal of our minds.

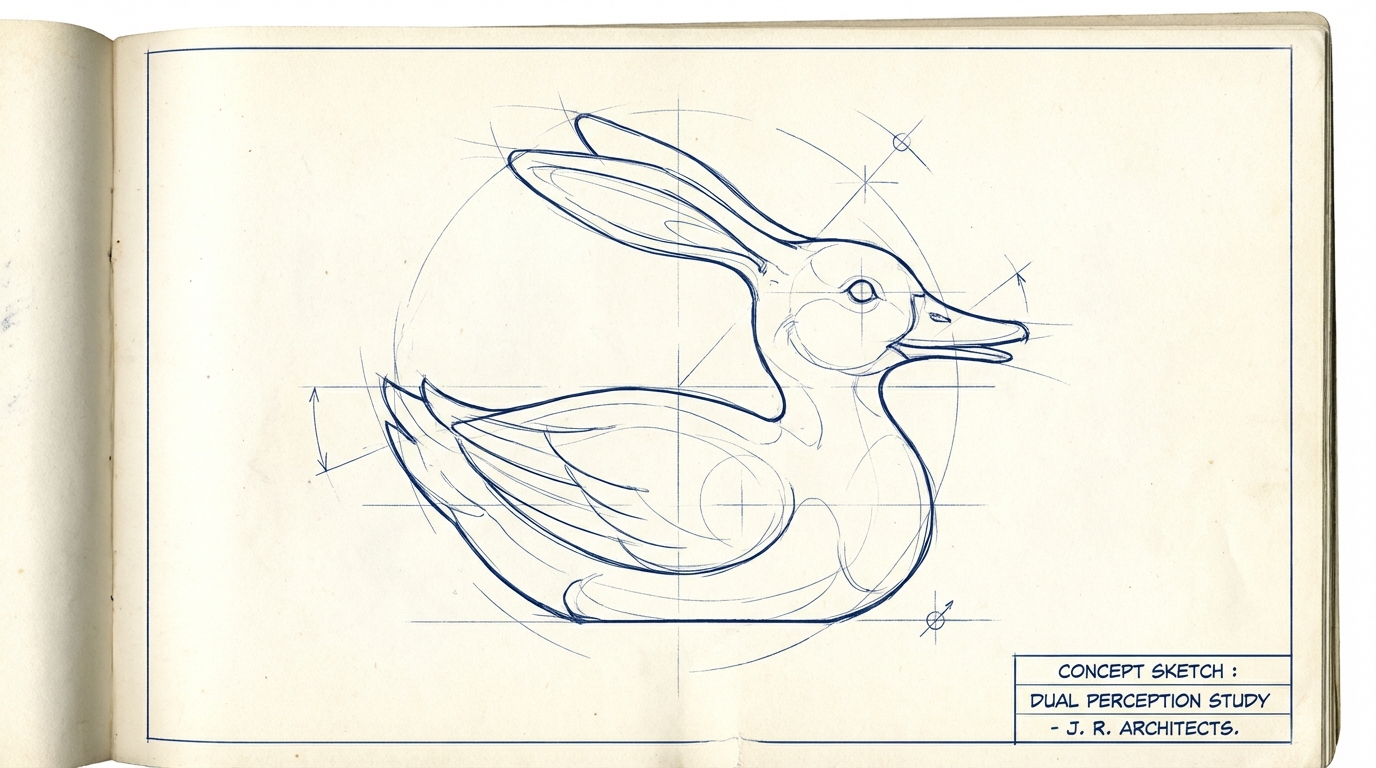

Seeing What Isn’t There

In 1892, psychologist Joseph Jastrow created an image that would become one of the most famous in perceptual psychology. The drawing shows a simple animal head. Look at it one way, and you see a duck facing left. Look again, and suddenly it’s a rabbit facing right. The remarkable thing isn’t that both interpretations exist in the same image—it’s that once you see one, it becomes nearly impossible to see the other until your perception shifts.

The duck-rabbit illusion demonstrates something profound about how we experience reality: we don’t passively receive information from the world; we actively interpret it. Our minds don’t function like cameras, impartially recording whatever passes before them. They work more like artists, constructing meaning from the raw data of experience according to patterns we’ve learned to expect.

Consider another example, one that affects everyday life more directly than any optical puzzle. Two people witness the same teenager walking through their neighborhood late at night, hands stuffed in the pockets of a dark hoodie. One observer thinks, Poor kid—must be walking home from a late shift at work. The other observer thinks, Better lock the doors—trouble coming. Same teenager, same time of night, same hoodie—radically different interpretations.

What accounts for the difference? Not the facts themselves. The difference lies entirely in what each observer brings to the encounter: their assumptions about teenagers, their experiences in that neighborhood, their background beliefs about human nature, their level of fear or trust. These invisible assumptions function like lenses, refracting the raw data of experience into meaningful shapes. Two people can look at identical circumstances and see completely different realities.

This is precisely what worldviews do. In the Introduction, we defined worldview as the lens through which we see and interpret everything—the operating system running in the background of our minds. But now we need to go deeper. Worldviews don’t just help us interpret the world; they actually shape what we’re capable of perceiving. Like the duck-rabbit illusion, they determine which patterns we notice and which remain invisible.

The question isn’t whether you have a worldview. Everyone does. The question is whether you’ve ever examined yours—and whether the lenses through which you see reality are helping you see clearly or distorting everything you look at.

How Worldviews Form

Nobody chooses their initial worldview. We absorb it the way we absorb language: gradually, unconsciously, through repeated exposure to the patterns that surround us. By the time we’re old enough to think critically about our assumptions, most of them are already in place.

Family provides the first and deepest layer. Long before we can articulate ideas about God, truth, or human nature, we’ve already absorbed messages from how our parents treated us, how they related to each other, how they responded to suffering, and how they spoke about the world. A child whose father rages when frustrated learns something about anger—and perhaps about God’s character—that no Sunday school lesson will easily undo. A child whose mother anxiously monitors every danger learns something about the world’s safety that will shape her responses decades later. These aren’t lessons taught with words; they’re lessons absorbed through experience, written into the emotional architecture of our minds before conscious thought begins.

Culture surrounds us from birth, saturating us with assumptions so pervasive we rarely notice them. The culture you grew up in taught you what counts as success, what emotions are acceptable to express, what body type is attractive, what kind of life is worth living, and a thousand other value judgments. These messages arrive through advertising, entertainment, social expectations, and the accumulated habits of your community. They’re in the water, as the saying goes—invisible but influential.

Education shapes us more formally, both in what’s taught and what’s assumed. Your schooling conveyed not just facts but a framework for organizing those facts—assumptions about which questions are worth asking, which methods produce reliable knowledge, and which conclusions are considered respectable among educated people. A student trained in materialist assumptions will process evidence differently than one trained in theistic assumptions, even if they’re looking at identical data.

Media functions as a constant tutor, especially in our current age. The stories we consume—whether in films, shows, podcasts, or social media feeds—model certain views of reality and marginalize others. They show us which characters to admire and which to distrust, which moral choices lead to flourishing and which lead to ruin, which versions of the good life are worth pursuing. This shaping happens largely below the level of conscious analysis; we don’t critically evaluate every plot point, so the assumptions embedded in our entertainment slip past our defenses.

Personal experience delivers perhaps the most powerful worldview messages of all. When tragedy strikes, our interpretation of that tragedy shapes our view of reality more than any sermon or lecture. If you prayed desperately for something and it didn’t happen, you drew conclusions about prayer—and perhaps about God’s character. If you trusted someone and were betrayed, you drew conclusions about human nature. These experiential lessons can override everything else we’ve been taught because they carry the weight of lived reality.

The result of all these influences is a complex web of assumptions that function automatically, filtering every new piece of information through patterns we learned long ago. We don’t experience this filtering consciously. We simply look at the world and see… what our lenses allow us to see.

How Worldviews Operate

The most striking feature of worldviews is how invisible they are to those who hold them. We rarely think about our worldview; we think with it. It’s the frame, not the picture—and frames are designed to be unnoticed.

This invisibility operates through several mechanisms.

First, worldviews function as interpretive defaults. When you encounter a new situation, you don’t carefully consider every possible explanation before landing on an interpretation. Your mind immediately supplies a default reading based on the patterns it has learned to expect. This happens faster than conscious thought, which is why your emotional response to a situation often arrives before you’ve had time to think about it. The interpretation is already in place; thinking comes later—if it comes at all.

Second, worldviews create confirmation bias. Once we hold a particular view of reality, we tend to notice evidence that confirms it and overlook evidence that challenges it. If you believe the world is fundamentally hostile, you’ll remember every slight and injustice while forgetting acts of kindness and generosity. If you believe God is distant and disapproving, you’ll interpret difficult circumstances as punishment while explaining away blessings as coincidence. We don’t do this deliberately; our minds simply weight evidence according to the patterns we’ve already accepted.

Third, worldviews determine what counts as plausible. Before we evaluate an argument, we unconsciously assess whether its conclusion seems reasonable. If someone claims to have experienced a miracle, you won’t evaluate the evidence neutrally; you’ll process it through your prior beliefs about whether miracles are possible. This is why people can look at identical evidence and reach opposite conclusions—they’re operating with different standards of plausibility, different notions of what’s even possible.

The Apostle Paul understood this dynamic. Writing to the Corinthians, he explained why the gospel seemed foolish to some and powerful to others: “The natural person does not accept the things of the Spirit of God, for they are folly to him, and he is not able to understand them because they are spiritually discerned” (1 Corinthians 2:14). The issue isn’t intelligence or access to evidence; it’s the framework through which evidence is processed. Different lenses produce different conclusions.

This is sobering news for anyone who thinks they’re simply perceiving reality as it is. None of us enjoy neutral, unfiltered access to truth. We all see through lenses. The question is whether our lenses are calibrated to reality or distorting it.

Unexamined Worldviews Christians Hold

Here’s where it gets uncomfortable: professing Christians are not exempt from worldview distortion. In fact, because we often assume that accepting Christ automatically corrects our thinking, we may be less vigilant about examining our actual operating assumptions.

Consider some examples of functional worldviews that coexist uneasily with professed faith.

The Prosperity Assumption. Many Christians functionally believe that faithfulness should produce material blessing. They may not articulate this as theology, but watch how they respond when finances tighten or health fails. Confusion, anger, a sense of betrayal—these emotional reactions reveal an underlying assumption that God owes comfortable circumstances to those who follow Him. This isn’t biblical faith; it’s a Christianized version of the prosperity gospel, absorbed more from cultural expectations than from Scripture. The Psalms are filled with faithful believers crying out in poverty and suffering; Job’s entire story shatters the equation of righteousness with prosperity. Yet the assumption persists because it resonates with our natural desire for security.

The Therapeutic Identity. Many believers functionally locate their identity in psychological categories—their feelings, their personal history, their self-perceived needs—rather than in their position in Christ. They speak the language of self-discovery, boundaries, and emotional needs with more fluency than the language of death to self, service, and cruciform love. When challenges arise, their first question is “What do I feel?” rather than “What is true?” This framework borrows from therapeutic culture while clothing itself in Christian vocabulary, and it produces Christians who are well-defended but poorly sanctified.

The Meritocratic Righteousness. Despite affirming justification by grace, many Christians functionally operate as if God’s favor depends on their performance. They’re anxious after failures, proud after successes, and constantly evaluating where they stand based on recent spiritual performance. This exhausting treadmill reveals a functional works-righteousness that contradicts everything we claim to believe about grace. The emotional fruit—anxiety, comparison, exhaustion—exposes the underlying worldview.

The Tribalistic Faith. Some Christians have adopted political or cultural identity as primary, with faith functioning as one component of a larger tribal allegiance. They’re more exercised about threats to their political party than threats to the gospel, more fluent in the talking points of their preferred media than in Scripture, more shaped by partisan narratives than by the biblical story. When faith and political loyalty conflict, faith bends—revealing which framework actually operates as the deepest lens.

These examples aren’t meant to condemn but to illustrate. The point isn’t that Christians who struggle with these patterns are insincere. It’s that sincerity doesn’t protect against distortion. We can genuinely love Jesus while still processing much of life through borrowed lenses. As Solomon wrote, “As a man thinks in his heart, so is he” (Proverbs 23:7 NKJV). What we actually believe at the heart level—our functional worldview—shapes who we actually are.

The Call to Transformation

This diagnosis would be discouraging if the Bible offered no remedy. But Scripture doesn’t merely describe the problem; it prescribes the solution.

“Do not be conformed to this world,” Paul writes to the Romans, “but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that by testing you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect” (Romans 12:2).

Three elements deserve attention here.

First, the warning: do not be conformed. The Greek word is syschematizo, from which we get “schematize”—to be pressed into a mold, to have your shape determined by an external pattern. The world—the system of values, assumptions, and priorities that operates apart from God—exerts constant pressure to conform. This isn’t occasional temptation; it’s continuous molding, the relentless shaping force of a thousand daily messages that push us toward certain ways of seeing and certain ways of living. Resistance requires awareness that the pressure exists.

Second, the command: be transformed. The word is metamorphoo, from which we get “metamorphosis”—a complete change of form, like a caterpillar becoming a butterfly. This isn’t modification or improvement; it’s fundamental restructuring. And notice the passive voice: we are to be transformed, not to transform ourselves. This change isn’t accomplished by willpower alone. It happens as we submit to a power beyond ourselves, as the Spirit works in us to reshape what we’re becoming.

Third, the method: by the renewal of your mind. The battlefield is the mind—not just conscious thoughts but the entire cognitive framework through which we process reality. The word for “renewal” (anakainosis) implies making new what has become old or worn out. Our minds have been corrupted by the fall and further distorted by cultural formation; they need comprehensive renovation.

Paul expands on this theme in Ephesians: “Put off your old self, which belongs to your former manner of life and is corrupt through deceitful desires, and be renewed in the spirit of your minds, and put on the new self, created after the likeness of God in true righteousness and holiness” (Ephesians 4:22-24). The old self isn’t just modified; it’s put off like a garment. The new self isn’t self-created; it’s created by God. And the process involves being “renewed in the spirit of your minds”—a deep renovation of the inner framework.

Similarly, Paul tells the Corinthians: “We destroy arguments and every lofty opinion raised against the knowledge of God, and take every thought captive to obey Christ” (2 Corinthians 10:5). This militant language—destroying, taking captive—suggests that worldview transformation isn’t passive. It requires active engagement, deliberately challenging assumptions that contradict what God has revealed.

The goal isn’t merely correct thinking but correct seeing—perceiving reality as it actually is, viewing ourselves, God, and the world through lenses properly calibrated to truth. When our worldview aligns with reality, our beliefs follow, our values follow, and our behavior follows. Transformation cascades from renewed vision.

The Process of Change

How does worldview transformation actually happen? If our assumptions were formed unconsciously over decades, can they really be changed?

The answer is yes—but the process is neither quick nor simple. Several elements are essential.

Exposure comes first. We must encounter biblical truth repeatedly, allowing Scripture to wash over our minds and confront our assumptions. This isn’t casual reading but immersive engagement—dwelling in the text, meditating on its claims, letting its categories reshape our instinctive responses. “Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly,” Paul writes (Colossians 3:16). The dwelling suggests something more than visiting; it implies taking up residence, becoming the atmosphere in which we live.

Examination follows. We must learn to notice our automatic interpretations—to catch ourselves reacting to circumstances and ask, “What assumption drove that reaction?” This requires cultivating a kind of metacognition, thinking about our thinking. When we feel angry, afraid, or anxious, we ask: “What would have to be true for this emotion to make sense? What am I functionally believing right now?”

Evaluation tests those assumptions against Scripture. When we identify a functional belief—“I deserve better than this,” “My worth depends on achievement,” “God has abandoned me”—we bring it before the Word and ask whether it aligns with what God has revealed. Often it doesn’t. The honest recognition of that gap creates opportunity for change.

Exchange replaces the false with the true. We don’t merely reject wrong assumptions; we consciously embrace right ones. When the old pattern surfaces, we deliberately rehearse the truth: “God is good even when circumstances are hard. My worth is grounded in Christ, not achievement. God has promised never to leave or forsake me.” Over time, with repetition, the new pattern begins to function as automatically as the old one did.

Community accelerates the process. Worldview transformation happens more readily in fellowship with others who share the journey. We need brothers and sisters who know us well enough to identify our blind spots, who love us enough to speak truth into our self-deceptions, and who walk alongside us through the slow work of renovation. Isolation makes us vulnerable; community makes us accountable.

Prayer undergirds everything. We cannot transform ourselves. We need the Spirit’s illumination to see our distortions, the Spirit’s conviction to acknowledge them, and the Spirit’s power to change them. The same God who shone light into darkness at creation can shine into our hearts “to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ” (2 Corinthians 4:6).

This process is lifelong. We won’t achieve perfect vision this side of glory. But incremental progress is possible—seeing a little more clearly today than yesterday, processing life through lenses a little better calibrated to reality. The goal isn’t perfection but direction: are we moving toward clearer sight or settling for comfortable distortion?

Finding the Right Standard

By now a critical question has emerged: If all of us see through lenses, if even Christians can hold distorted worldviews, where do we find a reliable standard? How do we know whether our lenses are properly calibrated?

This isn’t an abstract puzzle. It’s the most practical question imaginable. We can’t evaluate our worldview against nothing; we need a reference point outside ourselves. We need an authority trustworthy enough to challenge our assumptions, comprehensive enough to address all of life’s questions, and stable enough to stand when everything else shifts.

Some have claimed human reason as that authority—but reason itself operates through worldview lenses. Others have proposed science—but science tells us how things work, not why they matter or who we are. Still others suggest personal experience—but experience is precisely what gets filtered through the lenses we’re trying to evaluate.

The biblical claim is that God has spoken. He has revealed truth about Himself, about us, and about reality in a form we can access, examine, and trust. This revelation provides the fixed point outside ourselves that we desperately need—an authority capable of correcting our distortions rather than merely reflecting them.

But is this claim credible? Can we really trust that the Bible provides the reliable standard our examination requires?

That’s the question we must turn to next. Having understood how worldviews form and how profoundly they shape our perception, we need to investigate where we find truth reliable enough to correct our sight. The lenses need calibration—and the instrument we use must itself be trustworthy.

Reflection Questions

-

Think about your upbringing. What assumptions about God, life, and human nature did you absorb from your family before you were old enough to evaluate them?

-

What cultural messages have most shaped your sense of what makes a “good life”? How do these messages compare with biblical teaching?

-

Consider a recent situation where you reacted emotionally. What functional belief might have driven that reaction? Was that belief consistent with Scripture?

-

Which of the “unexamined worldviews Christians hold” described in this chapter do you recognize in yourself? What experiences might have contributed to forming that pattern?

-

What practices might help you become more aware of the automatic interpretations your worldview produces?

Key Takeaways

-

Worldviews don’t just help us interpret reality; they shape what we’re capable of perceiving, like the duck-rabbit illusion that determines which pattern we see.

-

We absorb our initial worldview unconsciously through family, culture, education, media, and personal experience—long before we’re able to evaluate it.

-

Worldviews operate invisibly as interpretive defaults, creating confirmation bias and determining what we consider plausible.

-

Even sincere Christians can hold functional worldviews that contradict their professed beliefs, producing anxiety, pride, tribalism, or therapeutic self-focus.

-

Transformation requires the renewal of our minds through exposure to Scripture, examination of our assumptions, evaluation against biblical truth, exchange of false beliefs for true ones, community support, and prayer.